'THE MAN KNOWN ONLY AS TARZAN': THE DEATH-STRUGGLES OF THE APE-MAN AND THE QUEST FOR THE NEO-JANE

'THE MAN KNOWN ONLY AS TARZAN': THE DEATH-STRUGGLES OF THE APE-MAN AND THE QUEST FOR THE NEO-JANE

The Pop Jungian mythos

As I have argued in my two earlier reviews, the 'deep' explanation for the continuing survival of Tarzan in the popular culture in the early 21st century-even if only in the form of an icon-is primarily due to the Jungian sub-text that governs the 'deep psychology' of the mythos: the story of Tarzan is a popularized version of the Jungian theory of the male archetype, or animus, re-told as the adventures of a jungle super-hero.

More precisely, the unifying archetypal story of  Tarzan is that of an ascending animus (the masculine principle) encountering and subsequently 'mating' with an equal and complementary descending anima (the female principle, personified by Tarzan's mate, the shadowy woman known only as 'Jane'). The 'story' of Tarzan and Jane is all about the 'adventures' of the primitive first-stage animus (purely physical man),

who undergoes the process of psychic integration (the advancement towards the higher orders of emotional and intellectual existence) as a result of his erotic/sexual contact with a descending higher level anima, who undergoes a parallel process of erotic descent to the first stage of primitive feminine sexuality (symbolized by 'Eve'): Tarzan leaves the jungle for civilization in order to mate with Jane, while Jane enters the jungle in order to undergo her own process of sexual liberation and erotic fulfilment realized through her transformative seduction of the Ape-Man.

Tarzan is that of an ascending animus (the masculine principle) encountering and subsequently 'mating' with an equal and complementary descending anima (the female principle, personified by Tarzan's mate, the shadowy woman known only as 'Jane'). The 'story' of Tarzan and Jane is all about the 'adventures' of the primitive first-stage animus (purely physical man),

who undergoes the process of psychic integration (the advancement towards the higher orders of emotional and intellectual existence) as a result of his erotic/sexual contact with a descending higher level anima, who undergoes a parallel process of erotic descent to the first stage of primitive feminine sexuality (symbolized by 'Eve'): Tarzan leaves the jungle for civilization in order to mate with Jane, while Jane enters the jungle in order to undergo her own process of sexual liberation and erotic fulfilment realized through her transformative seduction of the Ape-Man.

From this perspective, the most meaningful, and dramatically the very best, of the Tarzan films is the seminal Tarzan and His Mate (1934), which perfectly encapsulates within cinematic form all of the core elements of the archetypal tale of the animus/anima. However, as everyone knows, the quality, both cinematic and erotic, of the Tarzan films dropped off tremendously following the backlash of the censorship mechanisms put in place with the implementation of the Hays Code (1934-68).

In strictly Jungian terms, the Hay's Code, performing the role of censor, acted as a sort of psychic 'screening mechanism', preventing the infiltration into public consciousness the liberating and subversive erotic intensity of the unmediated 'primal scene' of the archetypal coeval union of animus with anima. Ostensibly a protest against the (remarkable) nudity in the film, the policing of the Tarzan series was really all about the only-slightly-disguised representation of pre-marital sexual relations between Tarzan and his Woman.

The public scandal created by Tarzan and His Mate in terms of the unconscious was that it was a 'naked' filmic demonstration of the vital necessity of the first-stage of erotic being for complete psychic health: the realization of the Garden/Eden. Although both Tarzan and Jane (Ape-Man and Jungle-Girl) are archetypal in their own terms, it is the 'mating' of the two that causes a fictional version of Africa to symbolically transform into a jungle version of Eden. Under the repressive regime of the Hays Code, however, both Tarzan and, even more so, Jane were effectively de-eroticized (that is, Jane was no longer half-naked), destroying the psychological meaningfulness of the cinematic versions of the characters and reducing the entire film series to both comedy and parody.

I argue, therefore, that none of the Tarzan films made between 1934 and 1959 are worthy of serious consideration (the sole possible exception is 1951's Tarzan's Peril,  which manages to weakly re-introduce the linked primal themes of Sex and Death, primarily through the iconic bondage scene with Dorothy Dandridge and a savage nocturnal knife fight in the jungle between Tarzan and a powerful tribal assassin. The other film of note, Tarzan's Fight For Life, is really only worth mentioning for one scene-the strangling of the supine and nubile Jane, Eve Brent-with a repulsive tribal garrotte).

which manages to weakly re-introduce the linked primal themes of Sex and Death, primarily through the iconic bondage scene with Dorothy Dandridge and a savage nocturnal knife fight in the jungle between Tarzan and a powerful tribal assassin. The other film of note, Tarzan's Fight For Life, is really only worth mentioning for one scene-the strangling of the supine and nubile Jane, Eve Brent-with a repulsive tribal garrotte).

The Deadly Dilemma of Sy Weintraub's Tarzan

The 'revival' (indicating a deliberate return to origins) of the Tarzan films by Sy Weintraub in the late 1950s provided the solution to the psychic block created by the Hay's Code: the elimination of Jane as an on-screen character and the re-establishment of the archetypal erotic sub-text. The elimination of Jane and the circumvention of the Hay's Code was effected through an erotically charged form of symbolic dis-placement. The internal erotic logic of Tarzan as the first-stage animus demands the presence of the corresponding anima, a higher-stage re-presented in the jungle as 'Eve'; the cinematic dilemma is that the re-introduction of Jane-as-Eve re-activates the screening mechanism of the Hay's Code. Weintraub's brilliant resolution was to have each of his films re-stage in some way the central elements of the primal Tarzan story: the union/mating of the animus with an anima that is always reconstituted as a new or strange woman who dramatically functions as the symbolic surrogate for Jane-Eve. Because there is no longer any danger of the audience witnessing Tarzan and his Woman existing in sinful co-habitation, the screening mechanism will never be triggered (other than the stricture of the most general Hollywood requirement of no explicit nudity). The crucial requirement is that the new woman-or the Neo-Jane-be able to dramatically work as an acceptable substitute for the now 'lost' Jungle-Girl; she must always be capable of dramatically equalling, or 'matching', the iconic Jane/Eve in her capacity to serve as the symbolic anima to the Ape-Man's animus. Although Tarzan and (the 'real') Jane are no longer together on screen, the erotic cinematic narrative devices of both Sex and Death are re-charged and moved to the very forefront of the action so as to enable the re-staging of the archetypal primal scene of the Tarzan mythos: the Ape-man risking everything and giving his all in order to win his sexually powerful mate. Throughout the Weintraub films the archetypal drama will be cinematically re-staged in the form of a 'challenge' to Tarzan; a challenge that always operates on two levels-the explicit challenge to the Ape-Man/animus on the conscious level in the form of a physically overwhelming masculine rival and the implicit challenge to Jane/anima in the form of a sexually irresistible new Woman. Both forms of the challenge serve as very real but slightly different forms of masculine film viewing pleasure: the heterosexual voyeuristic delight in identifying with Tarzan combined with a feeling of erotic pathos over the now 'lost' Jungle-Girl who has been symbolically 'killed off' by the even more erotically powerful Neo-Jane-and who will, in turn, be replaced by another.

Beginning with Tarzan's Greatest Adventure (1959), widely accepted as the best of the Weintraub films, if not the very best film of the entire series, we witness an original, and dramatically very startling, re-vitalization of the basic Tarzan film 'formula', one that was to be repeated on an even higher level in the other superior Weintraub film, Tarzan and the Valley of Gold (1966)-and, to a lesser degree, with all of the other Weintraub films. Both Adventure and Valley of Gold are centred upon:

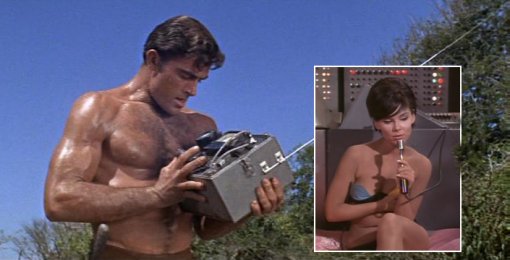

(i) Tarzan's initial encounter with an 'unknown' woman of utterly glamorous sexual beauty (Angie; Sophia Renault) who is not immediately linked to Tarzan but who will become his new 'mate' by the end of the film as a result of the outcome of;

(ii) Tarzan's climatic death-struggle with a hyper-masculine but sexually insecure villain who relates to Tarzan in both a clearly symbolic and psychologically meaningful way-mainly through his exhibiting of pronounced symptoms of sexual, or 'castration', anxiety. The villains in both films-the big-game hunter Slade and the international criminal Vinero, respectively-signal a clearly erotic sub-text; their hysterically exaggerated desire to kill the Ape-Man and demonstrate their own 'strength' is the externalization of their anxiety to prove their sexual superiority over the Ape-Man-as-animus. And it is Tarzan's desperate but final victory in this death-struggle that provides the link to the symbolic erotic union with the Neo-Jane.

Beginning with Tarzan's Greatest Adventure (1959), widely accepted as the best of the Weintraub films, if not the very best film of the entire series, we witness an original, and dramatically very startling, re-vitalization of the basic Tarzan film 'formula', one that was to be repeated on an even higher level in the other superior Weintraub film, Tarzan and the Valley of Gold (1966)-and, to a lesser degree, with all of the other Weintraub films. Both Adventure and Valley of Gold are centred upon:

(i) Tarzan's initial encounter with an 'unknown' woman of utterly glamorous sexual beauty (Angie; Sophia Renault) who is not immediately linked to Tarzan but who will become his new 'mate' by the end of the film as a result of the outcome of;

(ii) Tarzan's climatic death-struggle with a hyper-masculine but sexually insecure villain who relates to Tarzan in both a clearly symbolic and psychologically meaningful way-mainly through his exhibiting of pronounced symptoms of sexual, or 'castration', anxiety. The villains in both films-the big-game hunter Slade and the international criminal Vinero, respectively-signal a clearly erotic sub-text; their hysterically exaggerated desire to kill the Ape-Man and demonstrate their own 'strength' is the externalization of their anxiety to prove their sexual superiority over the Ape-Man-as-animus. And it is Tarzan's desperate but final victory in this death-struggle that provides the link to the symbolic erotic union with the Neo-Jane.

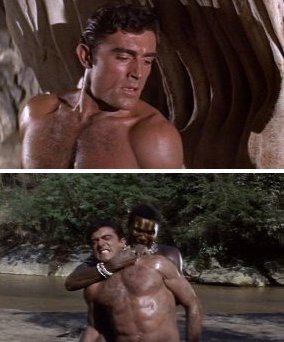

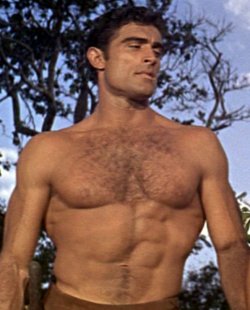

As with Tarzan and His Mate, the plot of Adventure is fairly simple and equally deceptive. Here, the explicit 'hunt' is for a lost diamond mine; the implicit hunt is the death of Tarzan (Gordon Scott). One of the most striking elements of Adventure is that the killing of the Ape-Man serves as the entire point of the narrative; Death is foregrounded as the defining rationale of the story, and the film is unusually effective in its powerful and suspenseful re-presentations of it, far beyond anything in any earlier Tarzan film and rivalled only by the later Valley of Gold and Tarzan and the Great River (1967).

As with Death, its erotic twin Sex is explicitly re-introduced and equally fore-grounded with both Tarzan and the villain, Slade (Anthony Quayle) having possessing an openly romantic relationship with their respective woman- the spoilt party-girl Angie (Sara Shane) and the Italian sex-kitten Toni (Scilla Gabel), who are shown as pitted against each other in an implicit sexual rivalry.

And, as we should expect, the drama of the 'erotic logic' of Jane is played out here as well-described by one prominent reviewer as 'approximately beautiful', Angie, while exceedingly lovely and clearly infatuated with Tarzan, is simply 'no match' for the Sophia Loren-esque Toni. The erotic competition between the two women, the cinematically stereotypical Good Girl (flirtatiously suggestive) and Bad Girl (narcissistically displaying), takes a decidedly phallic twist, as it becomes focussed upon rival symbolic demonstrations, primarily through the various motifs of hunting, of the physical superiority of their respective mates-a striking example of the erotic adage that the sexual power of a woman is measured by the physical prowess of their Man.

Given Tarzan's romantic relationship with Angie, highlighted by an extremely hot kissing scene with Tarzan (edited out in the American release of the film, the lingering effect of the Hays Code) the absence of Jane becomes even more dramatically troubling (and erotically provocative); the film expressly telegraphs Jane's elimination of and substitution by Angie by having Toni pointedly identifying the Good Girl as 'Tarzan's woman' (which elicits the sexually suggestive remark from Slade directed at both Tarzan and Jane: 'He [Tarzan] has better taste that I gave him credit for!').

As with Tarzan and His Mate, the plot of Adventure is fairly simple and equally deceptive. Here, the explicit 'hunt' is for a lost diamond mine; the implicit hunt is the death of Tarzan (Gordon Scott). One of the most striking elements of Adventure is that the killing of the Ape-Man serves as the entire point of the narrative; Death is foregrounded as the defining rationale of the story, and the film is unusually effective in its powerful and suspenseful re-presentations of it, far beyond anything in any earlier Tarzan film and rivalled only by the later Valley of Gold and Tarzan and the Great River (1967).

As with Death, its erotic twin Sex is explicitly re-introduced and equally fore-grounded with both Tarzan and the villain, Slade (Anthony Quayle) having possessing an openly romantic relationship with their respective woman- the spoilt party-girl Angie (Sara Shane) and the Italian sex-kitten Toni (Scilla Gabel), who are shown as pitted against each other in an implicit sexual rivalry.

And, as we should expect, the drama of the 'erotic logic' of Jane is played out here as well-described by one prominent reviewer as 'approximately beautiful', Angie, while exceedingly lovely and clearly infatuated with Tarzan, is simply 'no match' for the Sophia Loren-esque Toni. The erotic competition between the two women, the cinematically stereotypical Good Girl (flirtatiously suggestive) and Bad Girl (narcissistically displaying), takes a decidedly phallic twist, as it becomes focussed upon rival symbolic demonstrations, primarily through the various motifs of hunting, of the physical superiority of their respective mates-a striking example of the erotic adage that the sexual power of a woman is measured by the physical prowess of their Man.

Given Tarzan's romantic relationship with Angie, highlighted by an extremely hot kissing scene with Tarzan (edited out in the American release of the film, the lingering effect of the Hays Code) the absence of Jane becomes even more dramatically troubling (and erotically provocative); the film expressly telegraphs Jane's elimination of and substitution by Angie by having Toni pointedly identifying the Good Girl as 'Tarzan's woman' (which elicits the sexually suggestive remark from Slade directed at both Tarzan and Jane: 'He [Tarzan] has better taste that I gave him credit for!').

But the most powerful symbolic/erotic element in the film is the one introduced by the 'anxious' Slade who, significantly, is a world-class 'Big Game Hunter', and is, we assume, exceedingly self-conscious of his masculinity. The visual and symbolic centrepiece of the film is Slade's hand-crafted 'anti-Tarzan' weapon, a ghoulish noose that Slade will use to strangle Tarzan when the two meet in their (semi-) pre-arranged duel of hand-to-hand combat. Throughout the second half of the film, Slade-now a demented version of Ernest Hemmingway-ostentatiously displays the noose, treating it as an extension of his own being; he resembles nothing so much as Captain Ahab with his 'magic' harpoon, a fetish that symbolizes a sexual obsession the intensity and pathology of which can only represent the highest degree of phallic magnitude.

But the most powerful symbolic/erotic element in the film is the one introduced by the 'anxious' Slade who, significantly, is a world-class 'Big Game Hunter', and is, we assume, exceedingly self-conscious of his masculinity. The visual and symbolic centrepiece of the film is Slade's hand-crafted 'anti-Tarzan' weapon, a ghoulish noose that Slade will use to strangle Tarzan when the two meet in their (semi-) pre-arranged duel of hand-to-hand combat. Throughout the second half of the film, Slade-now a demented version of Ernest Hemmingway-ostentatiously displays the noose, treating it as an extension of his own being; he resembles nothing so much as Captain Ahab with his 'magic' harpoon, a fetish that symbolizes a sexual obsession the intensity and pathology of which can only represent the highest degree of phallic magnitude.

The 'status' of the noose is, of course, obvious: it is a phallic prop that Slade will use with savage ferocity in order to eliminate the source of his castration anxiety, the Ape-Man/animus. It is, therefore, not a coincidence that Tarzan is referred to more frequently as 'Ape-Man' in Adventure than in any other film. The very pointed use of this key term symbolizes both the archetypal status of Tarzan and his symbolic representation as an animal sacrifice: the ritualistic killing that follows the end of the hunt will be the death of the first-stage animus, when the Ape-Man will be put down by Slade. This final act will constitute the replacement of the first-stage Ape-Man with a new, second-stage animus-defined by Jung as the Man-of-Action, here by personified by Slade-as-The-Great-Hunter.

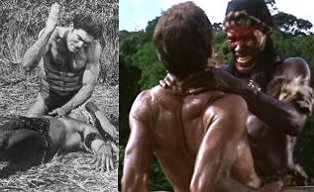

Indeed, the absolute centrality of the hunt/duel/killing motif is so great in this film that it should be re-titled Tarzan's Greatest Death-Struggle. As the film viewer has been led to expect, the extended climax of Adventure consists of one of the very best and most suspenseful of any of the fight sequences in the Tarzan film series. Adding to the suspense, Slade is the dominant combatant for the greater part of the fight, with the central action of the death-struggle consisting of the slow, painful, and ugly strangulation of the Ape-Man by The-Great-Hunter.

In a final strikingly symbolic moment, Tarzan is only able to deflect the lethal challenge of Slade at the last moment by turning the noose back against his would be killer, the fake first-stage animus Slade dying at the hands of the true first-stage animus Tarzan who wields Slade's own weapon-now openly exposed as a phallic prop-against him.

The 'status' of the noose is, of course, obvious: it is a phallic prop that Slade will use with savage ferocity in order to eliminate the source of his castration anxiety, the Ape-Man/animus. It is, therefore, not a coincidence that Tarzan is referred to more frequently as 'Ape-Man' in Adventure than in any other film. The very pointed use of this key term symbolizes both the archetypal status of Tarzan and his symbolic representation as an animal sacrifice: the ritualistic killing that follows the end of the hunt will be the death of the first-stage animus, when the Ape-Man will be put down by Slade. This final act will constitute the replacement of the first-stage Ape-Man with a new, second-stage animus-defined by Jung as the Man-of-Action, here by personified by Slade-as-The-Great-Hunter.

Indeed, the absolute centrality of the hunt/duel/killing motif is so great in this film that it should be re-titled Tarzan's Greatest Death-Struggle. As the film viewer has been led to expect, the extended climax of Adventure consists of one of the very best and most suspenseful of any of the fight sequences in the Tarzan film series. Adding to the suspense, Slade is the dominant combatant for the greater part of the fight, with the central action of the death-struggle consisting of the slow, painful, and ugly strangulation of the Ape-Man by The-Great-Hunter.

In a final strikingly symbolic moment, Tarzan is only able to deflect the lethal challenge of Slade at the last moment by turning the noose back against his would be killer, the fake first-stage animus Slade dying at the hands of the true first-stage animus Tarzan who wields Slade's own weapon-now openly exposed as a phallic prop-against him.

Out of Africa: Tarzan as the James Bond of the Jungle

Out of Africa: Tarzan as the James Bond of the Jungle

Tarzan's indisputable mastery of the jungle established in such spectacular fashion in Adventure created a serious narrative problem for the remaining films of the Weintraub series: how to maintain the dramatic 'intensity' of a repeatedly re-appearing super-hero? The follow up to Adventure, 1960s Tarzan the Magnificent, is something of a disappointment; although well-made and exceptionally suspenseful, the essential component of Eros is missing through making Tarzan woman-less, although Death is well served in the form of a series of savage fist-fights, including the finale in which leaves us to believe (falsely) that the villain has actually managed to beat the Ape-Man to death.

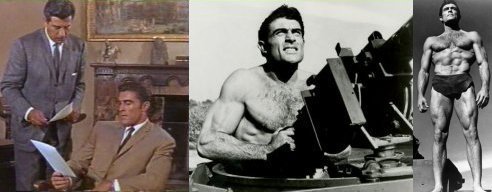

The solution that Weintraub settled upon was essentially the same one that Edgar Rice Burroughs came up with for the later Tarzan novels (the ones that follow the sequential Biography arc from Tarzan of the Apes to Tarzan the Invincible, which, in its original and 'truer' form, was centred upon the death of Jane): the archetypal Tarzan would shift from the first-stage animus to the second-stage, 'the civilized Man-of-Action'-physical man who has completely mastered all of the higher attributes of civilized behaviour, but retains the essential core of the primitive.

Now prominently single rather than monogamous (Jane having died in Tarzan the Invincible after having completed her dramatically/erotically necessary role of overseeing Tarzan's successful transition from first to second-stage, although she was very un-convincingly brought back to life in the next novel), the second-stage can continue his erotic quest for a mate far removed from his native Africa; in the later novels, Tarzan evolves into a free-lance adventurer unmoored from his traditional African landscape and immersed in fantastic settings (Pellucidar or wholly unexplored parts of Africa that strongly resembled Barsoom, Burrough's notion of the planet Mars) or, best of all, non-African locales (the Sahara; the Caribbean).

In literary terms, the Jungian archetype of the second-stage is Ernest Hemingway-the very figure that the psychotic Slade tries so hard to emulate and to succeed to in his prolonged death-struggle with Tarzan in Adventure. But if we were to turn to cinema, then the obvious filmic archetype of the second-stage would be: James Bond. Transforming Tarzan into a kind of 'James Bond of the Jungle' was a brilliant move: not only would Tarzan's natural course of psychic integration lead him down such a path, but the dramatic role played by the Secret Agent was fully consistent with the post-Jane Tarzan-as-Adventurer of the later novels-and which would, in fact, provide the narrative model for the later Weintraub films.

After the false starts of Tarzan Goes to India (1962) and Tarzan's Three Challenges (1963) which, while well-made and suspenseful, were, like Tarzan the Magnificent, dramatically marred by the absence of a seductive Neo-Jane, Weintraub achieved dramatic success with the first of the fully self-conscious of the James Bond/Tarzan hybrids: Tarzan and the Valley of Gold (1966). From now on, second-stage Tarzan is a 'secret agent' of the jungle performing dangerous missions, combatting emergent criminal or terrorist threats emerging in strange and exotic jungles all over the world; consequently, Tarzan's needs to periodically re-establish his true identity as the Lord of the Jungle over and over again, which forces him to re-connect directly with his first-stage 'essence'.

Tarzan-as-the-James-Bond-of-the-Jungle enables Weintraub to subliminally re-stage multiple variations of the archetypal Tarzan story: each 'deadly mission', is a re-enactment of the primal 'challenge' to Tarzan's identity as the true animus, (or alpha-male); as Weintraub brilliantly put it, 'When Tarzan kills, he is a worse killer than his enemy.' And, of course, the re-activation of Tarzan as animus narratively demanded the equally spectacular re-appearance of the anima,

now re-presented as the 'Tarzan-Girl', a hybrid of the off-screen (deceased? missing? separated?)

Jane and the generic 'Bond Girl'; the 'primitive' first-stage Jungle-Girl has now been replaced by a second-stage Tarzan-Girl, whose fetish outfit is no longer the loincloth (now displayed solely by Tarzan), but the provocative form-hugging/skin-tight lounge-style safari suit-a sex-fantasy costume wholly appropriate for a second-stage version of the Jungle-Girl.

now re-presented as the 'Tarzan-Girl', a hybrid of the off-screen (deceased? missing? separated?)

Jane and the generic 'Bond Girl'; the 'primitive' first-stage Jungle-Girl has now been replaced by a second-stage Tarzan-Girl, whose fetish outfit is no longer the loincloth (now displayed solely by Tarzan), but the provocative form-hugging/skin-tight lounge-style safari suit-a sex-fantasy costume wholly appropriate for a second-stage version of the Jungle-Girl.

The identification with James Bond, however, is mitigated by one vital consideration-because the dramatic impetus is the challenge to Tarzan, the monogamous Ape-Man's efforts are not about making love to the woman (unlike the polygamous Bond) but, rather, the exertion of his physical being to the utmost in order to 'win' the Neo-Jane as his 'new', and exclusive, mate. And it is this vital difference that best explains several of the most noticeable recurrent plot devices of the later Weintraub films with physically magnificent Mike Henry (and that spilled over into the Weintraub television series with Ron Ely): the Neo-Jane is always trapped in a form of bondage while Tarzan is being slowly strangled to death by the Challenger.

'A Stronger Man Can Make a Strong Man Weak': Death by Bare-Handed Strangulation

Strangulation equals complete control over the course of death; for the killer it is the most erotic form of killing, directly challenging the strength of the victim who is physically unable to break the hold. Also-the pressure against the throat can be continuously relaxed and then re-applied, prolonging the 'erotic agony' of the slow strangulation of the victim indefinitely for the sexually aroused killer. The male victim of bare-handed strangulation is, therefore, always feminized, or 'un-manned'. It is not by chance, then, that Adventure, the first of the serious Tarzan films, highlights the strangulation of the White-Ape caught in Slade's noose; there is in fact a powerful, if largely unconscious, form of erotic symbolism operating in the cinematic staging of Tarzan's death by bare-handed strangulation.

It constitutes the proof of the loss of alpha-male status to the challenger :when put to the absolutely final test, the Ape-Man proves too 'weak' to break the hold; there is no more certain way to signal his loss of identity as the animus than to have the Ape-Man die in the arms of his enemy. Even more dramatically it represents the 'loss' of the Tarzan's signature phallic symbol of the jungle cry, or the bull-ape cry of blood-lust triumph; in erotic terms, Tarzan's symbolic Achilles' heel is his throat and the crushing of his windpipe (or the breaking of his voice-box) is tantamount to the destruction of the Ape-Man's phallic power.

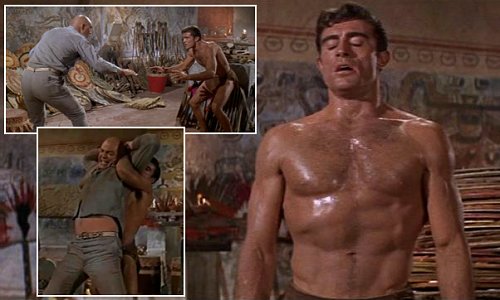

In Valley of Gold, which I have already discussed extensively in my first two reviews, the mode of Tarzan's death at the hands of the nefarious Mr. Train (based directly upon the super-killers Red Grant in From Russia With Love and Oddjob in Goldfinger) is not so much strangulation as 'death-grip'; during their prolonged combat, the mountainous bodyguard/hired-killer seems to be focussed on breaking Tarzan's neck-which, just as with Slade and his noose in Adventure, the Ape-Man is able to turn back against his would-be killer, trapping the obscenely powerful and skilled assassin in a lethal full-nelson. However, during the 'fast-motion' wrestling scenes during the death-struggle in the Chamber of Gold, Mr. Train's straddling atop the Ape-Man would appear to subliminally suggest a throttling of the White-Ape. Crushed wind-pipes and snapped neck vertebrae notwithstanding-and physical death by hideous means is always at the forefront in Valley of Gold-the shattering show-down at the end of the film is most notable for its generation of intense physical and erotic suspense through its impossible-yet-true violation of the 'boxer's body mass rule': under normal conditions, a combatant that is 25% larger should be able to 'drop' his lighter opponent with a single blow: we know from the press release that Tarzan is 240 lbs. and 6'4" while Mr. Train weighs in at 300 lbs. and 6'6" and, is, therefore, by 'rights' the guaranteed winner. The most suspenseful moment of the showdown, in fact, occurs just before the two alpha-males come to (death-) grips: after the White-Ape's surprise ambush/attack against Vinero's men with a tank, Mr. Train chases after Tarzan following him into the death-trap of the Chamber of Gold; in classic form, 'the hunter has become the hunter', indicative of Mr. Train's level of confidence in his ability to 'eliminate' the Ape-Man by 'tending' to him personally. Perhaps the surest proof of Mr. Train's status as Tarzan's greatest Challenger is simply this: the Ape-Man's total exhaustion at the end of the death-struggle, his failure to give the ultra-phallic bull-ape cry of triumphant blood-lust the outward sign of the unprecedented enormity of the threat of Death that he has, against all odds, triumphed over.

Since it was impossible to improve upon the 'phallic menace' of Mr. Train-and, therefore, by right Valley of Gold should have ended with Tarzan lying dead, face down, on the stone floor of the brutal death-trap that was the Chamber of Gold- in the next film, Tarzan and the Great River (1967), Weintraub decided that the only way to match the menace of the earlier challenger was to actually let the new villain, Barcuna subliminally 'kill' the Ape-Man in a

Since it was impossible to improve upon the 'phallic menace' of Mr. Train-and, therefore, by right Valley of Gold should have ended with Tarzan lying dead, face down, on the stone floor of the brutal death-trap that was the Chamber of Gold- in the next film, Tarzan and the Great River (1967), Weintraub decided that the only way to match the menace of the earlier challenger was to actually let the new villain, Barcuna subliminally 'kill' the Ape-Man in a  prolonged strangulation scene during the climatic death-struggle; given the agonizing duration and the animal ferocity of the jaguar-man's stranglehold on the White-Ape,

Tarzan would have 'had it' by the time his head was thrust downward below the bottom of the film frame (Tarzan's gasping animal sounds only add to the unconscious effect that we are witnessing the death of the jungle hero).

Although nowhere near as well-developed a super-villain as Mr. Train, Barcuna, the insane leader of an Amazonian tribe of blood-lusting 'jaguar-men', represents a kind of 'anti-Tarzan'; it is, in fact, Tarzan's secret mission to hunt down and kill the imposter version of himself. Promiscuously displaying a jaguar-skin loincloth even more spectacular than Tarzan's, Barcuna personifies the dark-animus the Ape-Man would have become if he had not undergone the psychic initiation provided by Jane but had instead allowed himself to be seduced by the dark-anima La, the High Priestess of Opar. Although less successful than Valley of Gold overall, Great River is noteworthy for its pronounced employment of phallic symbolism.

In a critical scene Barcuna stands menacingly over Great River's Neo-Jane, Dr. Ann Phillips, driving his jaguar-mace into the ground before her, who is both horrified and transfixed (in very much the same way that Sophia gasps out loud, physically disgusted, when witnessing Mr. Train's hideous demonstration of impossible strength in Valley of Gold); in fact, the entire scene is a subliminal enactment of rape (it is also a disguised challenge to Tarzan: Barcuna lets 'Jane' live in order to allow her to convey to her Mate the message that 'the jungle belongs to Barcuna!' Both Barcuna and Mr. Train seem to using the Neo-Jane to send death-threats to Tarzan.) When Tarzan offers combat to Barcuna, he does so by pointedly declaring 'I challenge Barcuna-man to man!'

And, as with Slade's noose, the jaguar-mace doubles as both a phallic prop and a phallic symbol-at the end, it is shown to be a mere prop when the barely victorious Tarzan consigns it to the flames; an act of alpha-male supremacy that is 'magically' re-enforced by the appearance of the lion-one of Tarzan's key phallic symbols-signifying Tarzan's status as the true HE-MAN of the Jungle.

prolonged strangulation scene during the climatic death-struggle; given the agonizing duration and the animal ferocity of the jaguar-man's stranglehold on the White-Ape,

Tarzan would have 'had it' by the time his head was thrust downward below the bottom of the film frame (Tarzan's gasping animal sounds only add to the unconscious effect that we are witnessing the death of the jungle hero).

Although nowhere near as well-developed a super-villain as Mr. Train, Barcuna, the insane leader of an Amazonian tribe of blood-lusting 'jaguar-men', represents a kind of 'anti-Tarzan'; it is, in fact, Tarzan's secret mission to hunt down and kill the imposter version of himself. Promiscuously displaying a jaguar-skin loincloth even more spectacular than Tarzan's, Barcuna personifies the dark-animus the Ape-Man would have become if he had not undergone the psychic initiation provided by Jane but had instead allowed himself to be seduced by the dark-anima La, the High Priestess of Opar. Although less successful than Valley of Gold overall, Great River is noteworthy for its pronounced employment of phallic symbolism.

In a critical scene Barcuna stands menacingly over Great River's Neo-Jane, Dr. Ann Phillips, driving his jaguar-mace into the ground before her, who is both horrified and transfixed (in very much the same way that Sophia gasps out loud, physically disgusted, when witnessing Mr. Train's hideous demonstration of impossible strength in Valley of Gold); in fact, the entire scene is a subliminal enactment of rape (it is also a disguised challenge to Tarzan: Barcuna lets 'Jane' live in order to allow her to convey to her Mate the message that 'the jungle belongs to Barcuna!' Both Barcuna and Mr. Train seem to using the Neo-Jane to send death-threats to Tarzan.) When Tarzan offers combat to Barcuna, he does so by pointedly declaring 'I challenge Barcuna-man to man!'

And, as with Slade's noose, the jaguar-mace doubles as both a phallic prop and a phallic symbol-at the end, it is shown to be a mere prop when the barely victorious Tarzan consigns it to the flames; an act of alpha-male supremacy that is 'magically' re-enforced by the appearance of the lion-one of Tarzan's key phallic symbols-signifying Tarzan's status as the true HE-MAN of the Jungle.

In the final Weintraub film, Tarzan and the Jungle Boy (1968), the Ape-Man's deadly confrontation with the Challenger, the incredibly powerful Prince Nagambi (Raefer Johnson, here repeating his role as the anti-Tarzan Barcuna), is noteworthy in the two ways that we should by now expect: (i) Nagambi repeatedly places the Ape-Man in a stranglehold, and (ii) the death-struggle is fought out in direct view of the sexually lascivious Myrna Claudel who, like both Sophia and Ann, is in bondage and awaiting imminent death-in this case, beheading (!) at the hands of the victorious Nagambi. A disappointing film in many ways, Jungle Boy does serve one very important narrative function-it lays the groundwork for the integration of the 'Jane-less' Weintraub movies and TV series into the overall Tarzan mythos.

I refer to the following passage taken from the one of the reviews posted at the IMDb blog spot of the film.

In the final Weintraub film, Tarzan and the Jungle Boy (1968), the Ape-Man's deadly confrontation with the Challenger, the incredibly powerful Prince Nagambi (Raefer Johnson, here repeating his role as the anti-Tarzan Barcuna), is noteworthy in the two ways that we should by now expect: (i) Nagambi repeatedly places the Ape-Man in a stranglehold, and (ii) the death-struggle is fought out in direct view of the sexually lascivious Myrna Claudel who, like both Sophia and Ann, is in bondage and awaiting imminent death-in this case, beheading (!) at the hands of the victorious Nagambi. A disappointing film in many ways, Jungle Boy does serve one very important narrative function-it lays the groundwork for the integration of the 'Jane-less' Weintraub movies and TV series into the overall Tarzan mythos.

I refer to the following passage taken from the one of the reviews posted at the IMDb blog spot of the film.

Tarzan's background very much parallels that of the jungle boy. A prime example of this is found during one of their one-on-one talks. Tarzan briefly mentions being an orphan of the jungle himself, taken to civilization, and making his decision of returning to Africa after reaching manhood. Though there's no mention of [his] being Lord Greystoke as depicted in the Tarzan stories, there's a clue of his being educated in city schools before resuming his life-style as a jungle-man.

It would be precisely within this background narrative 'space' that the now off-screen Jane could be located: she would be the very young adolescent girl who provided the required sexual 'bait' that lured the equally juvenile 'ape-boy' into the trap of civilization and causing him to undergo the necessary psychic transformation into the second-stage animus.  (Note: In my previous review, I suggested that Jenny Agutter would have made a perfect Jane if the Weintraub series had continued into the early 1970s; her iconic role in the Peter Weir film Walkabout proves her ideal status as an under-age Jane). And, as like the Jane of the later Tarzan novels, the off-screen Jane would maintain a long-range relationship with her Mate (whether married or merely lovers),

Tarzan periodically returning to his native Africa for extended solo adventures in order to maintain replenishing contact with his inner self of the first-stage.

(Note: In my previous review, I suggested that Jenny Agutter would have made a perfect Jane if the Weintraub series had continued into the early 1970s; her iconic role in the Peter Weir film Walkabout proves her ideal status as an under-age Jane). And, as like the Jane of the later Tarzan novels, the off-screen Jane would maintain a long-range relationship with her Mate (whether married or merely lovers),

Tarzan periodically returning to his native Africa for extended solo adventures in order to maintain replenishing contact with his inner self of the first-stage.

'A Man Should Always Have His Woman With Him': The Neo-Janes

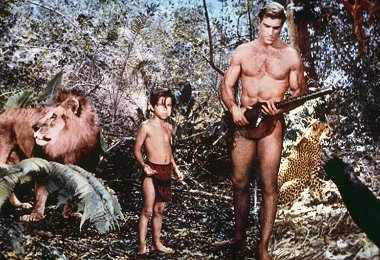

The title of this sub-heading is a direct quote made by Vinero to his sex-trophy mistress Sophia Renault in Valley of Gold.  If Sophia Renault is truly Jane's sexual superior, then it is not Vinero (symbolized by Mr. Train as an extension of Vinero's sadism and psychotic lust for power and 'strength') but Tarzan who is the 'weaker' man. Much of the erotic thrill of Valley of Gold lies with the suspense that is generated in the viewer's mind that Sophia has desperately gambled her only chance for life on the physically weaker man, who is contemptuously referred to by Vinero as 'the African' or, more provocatively, 'the so-called Ape-Man'; 'weaker', that is, only in comparison to the inhuman Mr.Train.

Also noteworthy is the extreme ease with which Sophia assumes the role of 'Jane' after she has been (temporarily) saved from Death by the White-Ape: she treats the ferocious lion, one of the Ape-Man's signature phallic symbols, as a pet and displays clearly maternal concerns for 'Boy' (the 'lost' jungle child Ramel), resulting in the remarkable re-creation of the 'Tarzan Family', which now has been successfully re-eroticized through the suspenseful interweaving of the archetypal themes of Sex (Sophia's world-class body in bondage) and Death (the physically 'invincible' Mr. Train who promises to kill the Ape-Man for his perverted master). In fact, the subliminal impression is created in the cinematic unconscious of the viewer that Sophia really is Jane,

having been kidnapped by Vinero at the start of the film and used as 'bait' to lure the Ape-Man into a death-trap: the utterly suspenseful and nakedly erotic scene of the booby-trapped necklace and Tarzan's desperate attempt to 'de-activate' the hellish thing (in fact, a 'fetish' of Vinero's lust, sadism and sexual perversity). If Weintraub had wanted to have been 100% faithful to the later Tarzan novels, wherein Tarzan and Jane seem to be enjoying a 'long-range' relationship, Valley of Gold easily could have started with Tarzan arriving in Acapulco to investigate the recent and mysterious disappearance of Jane; furthermore, it would have been Jane, having somehow learned of Vinero's criminal plans to kidnap the jungle boy and loot the Valley of Gold, who summoned Tarzan to Mexico in order to perform his deadly secret mission.

If Sophia Renault is truly Jane's sexual superior, then it is not Vinero (symbolized by Mr. Train as an extension of Vinero's sadism and psychotic lust for power and 'strength') but Tarzan who is the 'weaker' man. Much of the erotic thrill of Valley of Gold lies with the suspense that is generated in the viewer's mind that Sophia has desperately gambled her only chance for life on the physically weaker man, who is contemptuously referred to by Vinero as 'the African' or, more provocatively, 'the so-called Ape-Man'; 'weaker', that is, only in comparison to the inhuman Mr.Train.

Also noteworthy is the extreme ease with which Sophia assumes the role of 'Jane' after she has been (temporarily) saved from Death by the White-Ape: she treats the ferocious lion, one of the Ape-Man's signature phallic symbols, as a pet and displays clearly maternal concerns for 'Boy' (the 'lost' jungle child Ramel), resulting in the remarkable re-creation of the 'Tarzan Family', which now has been successfully re-eroticized through the suspenseful interweaving of the archetypal themes of Sex (Sophia's world-class body in bondage) and Death (the physically 'invincible' Mr. Train who promises to kill the Ape-Man for his perverted master). In fact, the subliminal impression is created in the cinematic unconscious of the viewer that Sophia really is Jane,

having been kidnapped by Vinero at the start of the film and used as 'bait' to lure the Ape-Man into a death-trap: the utterly suspenseful and nakedly erotic scene of the booby-trapped necklace and Tarzan's desperate attempt to 'de-activate' the hellish thing (in fact, a 'fetish' of Vinero's lust, sadism and sexual perversity). If Weintraub had wanted to have been 100% faithful to the later Tarzan novels, wherein Tarzan and Jane seem to be enjoying a 'long-range' relationship, Valley of Gold easily could have started with Tarzan arriving in Acapulco to investigate the recent and mysterious disappearance of Jane; furthermore, it would have been Jane, having somehow learned of Vinero's criminal plans to kidnap the jungle boy and loot the Valley of Gold, who summoned Tarzan to Mexico in order to perform his deadly secret mission.

As a former Miss Israel and a 'Bond Girl' in her own right (playing a gypsy princess in From Russia With Love) Aliza Gur (Myrna Claudel), the Neo-Jane of the 'Tarzan Family redux' of Jungle Boy is arguably potent enough to hold her own against the world-class beauty of Nancy Kovack in her subliminal competition for Tarzan's attention. As with Sophia, Myrna's erotic 'attraction' to Tarzan is immediate (after the Ape-Man discovers her dangling provocatively from the trees attached to a parachute) and her semi-comic dynamic with her sexually frustrated suitor Ken Matson, who has been clearly 'out-manned' by Tarzan, implicitly recalls the doomed pursuit of Jane by the 'masculinity-challenged' Harry Holt in Tarzan and His Mate.

But of far greater interest is the Neo-Jane of Great River, Dr. Ann Phillips played by

As a former Miss Israel and a 'Bond Girl' in her own right (playing a gypsy princess in From Russia With Love) Aliza Gur (Myrna Claudel), the Neo-Jane of the 'Tarzan Family redux' of Jungle Boy is arguably potent enough to hold her own against the world-class beauty of Nancy Kovack in her subliminal competition for Tarzan's attention. As with Sophia, Myrna's erotic 'attraction' to Tarzan is immediate (after the Ape-Man discovers her dangling provocatively from the trees attached to a parachute) and her semi-comic dynamic with her sexually frustrated suitor Ken Matson, who has been clearly 'out-manned' by Tarzan, implicitly recalls the doomed pursuit of Jane by the 'masculinity-challenged' Harry Holt in Tarzan and His Mate.

But of far greater interest is the Neo-Jane of Great River, Dr. Ann Phillips played by  Diana Millay: like Sara Shane in Adventure, Millay is utterly beauteous but 'second rate', or only 'approximately beautiful', in comparison to the multiple beauty contest winners Nancy Kovack and Aliza Gur. Erotically, Ann is the 'weakest' of the three women, which is precisely why she is the one Neo-Jane who most closely resembles the original or 'true' Jane; also, she is a medical doctor, a humanitarian profession consistent with Jane as both a descending and a light anima. Sophia Renault, although clearly charming, intelligent and well educated, remains nothing more than an exceptional sex-trophy-although clearly 'one to die for'.

Diana Millay: like Sara Shane in Adventure, Millay is utterly beauteous but 'second rate', or only 'approximately beautiful', in comparison to the multiple beauty contest winners Nancy Kovack and Aliza Gur. Erotically, Ann is the 'weakest' of the three women, which is precisely why she is the one Neo-Jane who most closely resembles the original or 'true' Jane; also, she is a medical doctor, a humanitarian profession consistent with Jane as both a descending and a light anima. Sophia Renault, although clearly charming, intelligent and well educated, remains nothing more than an exceptional sex-trophy-although clearly 'one to die for'.

Erotic Epilogue

For the sake of argument, it is possible to reconcile the Ape-Man's (implied) on-screen adultery with the continuing existence of the off-screen Jane in a manner consistent with the 'dark anima' aspects of both Tarzan and his Mate; the White-Ape's successful 'winning' of new and strange women through the bare-handed killing of his deadly Challengers actually appeals to the narcissistic and post-adolescent sexual ego of the exhibitionist Englishwoman who is ritualistically waiting for her lover's episodic return from the primeval jungle. The primal strength of Jane's primitive sexuality is continuously re-enforced by Tarzan's proven ability to conquer any woman he desires while always returning to his Mate, the archetypal half-naked Jungle Girl, in the end.

It is not unknown for a sexually narcissistic woman to derive intense voyeuristic thrills from hearing her lover's first-hand accounts of his 'erotic adventures' while off on his own.

A woman, in fact, uncommonly like Miss Moneypenny.

- reviewed by Eric Wilson